Matt Foss, associate professor of theater, stood at the helm of the Hartung Theatre on Tuesday night and addressed the cast of the upcoming theater production, “Medea.” It was the second week of rehearsal and students sat spread out, awaiting instruction from the theater department faculty member and “Medea” co-director.

Foss stepped forward as he told the cast, “Today, we will be appropriating a hip hop song, and this is how you’ll learn it,” the audience smiled.

“In case you don’t know it,” Foss said. “Listen to this,” the music began to play.

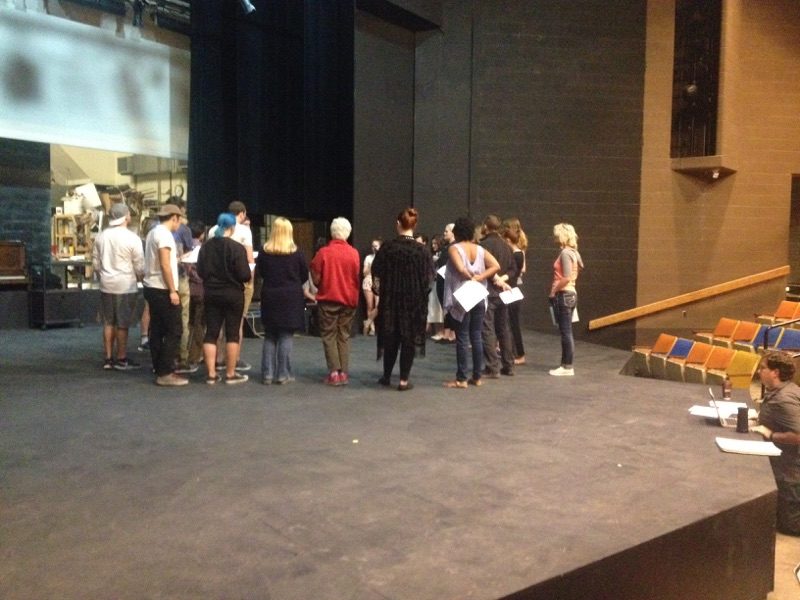

Corrin Bond | Argonaut

The cast of Medea collectively bonds moments before the rehearsal begins.

“Medea” is one of six productions the University of Idaho Theatre Department will produce this academic year.

Foss said unlike other productions, this play is being developed organically.

“Medea” was prompted by two faculty members within the UI Theatre Department. He said he and the play’s production team began by conducting extensive research on the Medea myth.

“We have a very famous group of myths and plays about Medea and working with Maiya Corral, a BFA senior in theater, we did extensive research on all of the variants of the myth,” Foss said. “Everything from Ovid to small fragments of poetry found on papyrus somewhere. We found all of the ways Medea’s story had been told.”

From there, Foss said the play developed in a more abstract way as elements belonging to different variations of the Medea myth were combined into one text and collaboration was incorporated into the production.

“To some that’s very scary and may even seem unconventional,” Foss said. “Shakespeare has a similar method, where he took different sources and was essentially writing with and for his friends. We may not have his skill set, but we’re trying to honor that tradition.”

While “Medea” has a more unconventional development, Foss said there is no correct way to produce a play.

“There’s no real right way to start a play or even to make it,” Foss said. “There’s probably a lot of wrong ways, but anything theater is such an immediate thing. We work hard for a long time, do it for a couple of nights, and then it’s over. In order for it to be a living, breathing thing, those types of projects start in any number of ways.”

Sean Hendrickson, the assistant director of the upcoming productions “Titus Andronicus” and “A Christmas Carol,” said the plays he is working on are being produced in ways that differ from “Medea.” Hendrickson, a fourth year BFA in performance, said the production process a play undergoes often depends on the story that’s being told.

He said the theater department has a certain number of slots reserved for productions each academic year. Those slots are then filled by students or faculty members who submit plays.

“The faculty might say, ‘We’re looking for a one-hour show that can happen in this space’,” Hendrickson said. “And students can share ideas they have.”

Hendrickson said the development of “Titus Andronicus” began after the play was proposed to the theater department by a graduate student. One year ago the student’s adaptation was accepted by the theater department and production for the play began. Hendrickson said “Titus Andronicus” had a more structured and conventional beginning than a play like “Medea.”

“The ‘Medea’ project is actually very different than ‘Titus,’” Hendrickson said. “One, our design faculty came to Kelly Quinnett, one of our performance faculty, with something new he wanted to work with. He wanted to try something different with the Medea myth and now they’re making this in a much more organic and less structured way.”

Among the reasons why so many different plays are produced in different ways is that each story has a different history, Hendrickson said.

“A lot of the reasons why these processes are so varied for each production are because of the consideration for the story we’re telling,” Hendrickson said. “In the case of ‘Medea,’ we’re looking at a myth that has been mistreated and misrepresented for centuries and has been distilled and reduced by a lot of dead white guys.”

Hendrickson said when production teams work with a play like “Medea,” they consider all possible ways to tell the story in a different light.

When it comes to producing a play from beginning to end, Hendrickson said the strongest factor in how to develop the play is why the story is being told in the first place.

“We work on a play like ‘A Christmas Carol’ and we have one definitive source text, but we also have to consider our audience’s experiences with the story as well as past ways it’s been produced,” Hendrickson said. “You know, more of the community probably has more of a relationship with the Muppet’s ‘A Christmas Carol’ than they do with Charles Dickens’ novel, we also have to consider why we’re telling the story.”

Corrin Bond

can be reached at

or on Twitter @CorrBond